I'm reading the monumental Abstraction And Comics (Volume I) published by the Presses Universitaires de Liège and the Cinquième Couche and I'm surprised to see that those who wrote the essays barely mention any abstract comics and those who drew and wrote them created no abstract comics at all. This is strange indeed...

Flipping through volume one, I see: "O Arco Da Noite Branca" by Diniz Conefrey, an untitled comic by Renaud Thomas, pages by El Lissitzky and Jean Ache, comics by Jessie Bi, comics by Kym Tabulo, a couple of pages by Benoit Joly, a page by Mark Gonyea, a few pages by Gene Kannenberg and that's about it in a 450 pages book.

It's baffling to read this, for instance: "Here we encounter tall buildings, rising water, a dog that gets encapsulated by strands of material that solidify out of smoke or streams of ants." (286) If we encounter all those things one thing we certainly don't encounter is abstraction, that's for sure...

By the way, the opposite of "abstraction" is "figurative" or "representational," not "narrative." The least we can say is that this is a "creative" use of words...

More later...

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Friday, November 15, 2019

Tom Spurgeon

Today I'm incredibly sad! I just learned that Tom Spurgeon died two days ago! You will be missed, Tom! I surely will miss you, my friend!...

Saturday, June 22, 2019

(Not Quite) The End

A little bug is flying around my head saying repeatedly to me that it's time to put this blog to rest. Looking back I fondly remember my arrival on the Internet, searching immediately for The Comics Journal site (it was 1997 or 1998, I can't remember anymore). I also fondly remember the comix@ list and the comixschl list (to which I belong to this day). I'm very grateful for these more than twenty years on the Internet, half writing this blog, but also for the opportunity to write for The Comics Journal for a brief period of time (something I couldn't imagine in my wildest dreams).

Now I must thank a lot of people:

The great José Muñoz, for giving me the honor of addressing his wonderful and unforgettable emails to me!

My gracious opponents: Kim Thompson (who left us way too soon and I miss terribly) and Tom Spurgeon on the CJ messboard and Arthur van Kruining on the comix@ list.

Noah Berlatsky, for letting me write on his blog The Hooded Utilitarian (that put me on the map, like I never was before or after). Matthias Wivel and Ng Suat Tong, for being there (love you guys!).

Håvard S. Johansen for inviting me to Comix Expo 2012 (loved it!).

Ann Miller, for her invitation to write in the European Comic Art magazine.

Frank Aveline, for inviting me to write in L'Indispensable.

Bill Kartalopoulos for my participation on the Alternative Comics site.

John Lent, for letting me publish in the International Journal of Comic Art.

Paul Gravett, for including me in his project 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die.

Marcos Farrajota, José Rui Fernandes and Julio Moreira for my inclusion in their Lisbon and Porto convention catalogs and Quadrado magazine. I must also thank Marcos for letting me be the curator of a Guido Buzzelli exhibition in Lisbon and José Rui for a great trip to New York!

Pedro Moura, Carlos Pessoa and Sara Figueiredo Costa for my inclusion in the Amadora convention catalog. I also thank Pedro for my inclusion in the Tinta nos Nervos exhibition catalog and several panel invitations.

Isabel Carvalho, Pedro Nora and Mário Moura for Satélite Internacional. Where have all those magazines gone?

Last, but not least, on the contrary, Miguel Falcato Alves and Manuel Caldas for publishing my first writings, insipid as they were...

Also: my supporters when the world was against me: you know who you are...

Damn you world, for giving me such a hard time! You also know who you are.

A big thank you goes to my faithful readers. I which I could say it personally to each and everyone of you! (Surely, you aren't that many...)

Will this be my last post on this blog or is my comics critic career over? I don't know, maybe... I'll write here whenever I feel like (once in a blue moon, I guess) and my days as comics critic are out of my hands. It all depends on putative invitations, but I will be forgotten, I'm sure I will... When you fight against the whole world you're sure to lose, but, as António Dias de Deus put it: the only victory possible is defeat. See you in the funny papers... Oh, and, you know... this art form deserves to die...

Monday, June 17, 2019

Breaking The Frames - Coda

Because of this post I just reread what I wrote about The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Baetens and Frey. Man! I miss myself!

The conclusion:

The conclusion:

This book is a sad sign of the barbarian neoliberal times in which we are unfortunately living in. If you think that the political reference is uncalled for, think harder. With education systems running at double speed: with good schools for the wealthy; and crappy underbudgeted schools for the 99 %... With a capitalistic world view in which only what sells is worth doing resulting in a culture running at double speed also: with sophisticated art for the 1 % paid at its weight in gold; and the lousy lowest common denominator for everybody else... It's no surprise that a future which once looked like this (you may notice that Jan Baetens was supposed to be part of it), is now ashamed of itself (it's elitism) trying desperately to backpedal to square one.This art form deserves to die.

Friday, June 14, 2019

Breaking The Frames

With the exception of Chris Ware the artists whose work is examined (with metacriticism to boot too; the best part, I must say...) don't interest me in the least (or, to be more precise, in Alan Moore's case, his work examined doesn't interest me because I just like From Hell and not much else). That said I would love to see the criticism of such a sacred cow as Jack Kirby debunked, for instance, but beggars can't be choosers and I'm perfectly happy with what I got.

OK, so, Chris Ware: Marc Singer is unfair to him because, in the end, he accuses him of being a coherent editor. Imagine that, he is an editor with a taste and aesthetic standards! The horror! Right?!... On the other hand Chris Ware's taste isn't as narrow as Marc Singer suggests. He likes the work of Frank King and George Herriman, among many other things like Suiho Tagawa's comics or The Kin-Der Kids. Are all these artists already dead? They are, for many years now, and, maybe, that's why Chris Ware didn't include their work as the best of 2007?

Does Marc Singer incur in the same mistakes he accuses others of? Unfortunately, the answer is yes. For instance: he chastises those who say that Marjane Satrapi chose to publish in black and white when economical considerations on the L'Asso's part are 100% responsible for that choice, but on page 130 he wrote "Witek acknowledges that the artwork in Pekar's comics is often crude, unsophisticated, not "conventionally 'realistic'"-with the stylistic descriptor placed in quotes, as if to signal that the comic's realism lies in areas other than visual convention." Harvey Pekar's stories are often crudely drawn because he couldn't afford the artists he really liked. Two things, here though: 1) I seem to remember Harvey Pekar saying something to that effect, but I'm not sure (it's been a while); 2) on the other hand he couldn't criticize "his" artists, could he?, but I believe he genuinely liked some of them - here he praises a few, but what's interesting to me is that he excuses Robert Crumb's cartoony style because his work is a "wealth of accurately observed detail". This proves to me that he didn't get what he wanted most of the times, not even from Crumb...

Tuesday, May 21, 2019

Dumbing Down

I haven't seen the exhibition, but I bet that, after seeing it I would agree with every word.

The only Japanese comics artists I really like (in the restrict field, I mean...) are Taniguchi and Tsuge, anyway...

The only Japanese comics artists I really like (in the restrict field, I mean...) are Taniguchi and Tsuge, anyway...

Wednesday, May 15, 2019

Seth

I undestand what Seth says at the beginning (the interview starts at 9:40): the thrill of seeing your work in print kind of fades with age. That's kind of sad, I guess, but that's life, we get more and more detached...

Monday, April 29, 2019

Monthly Stumblings #20: Jochen Gerner

Panorama du feu (a view of fire) by Jochen Gerner

Jochen Gerner was a founding member of the OuBaPo (Ouvroir de Bande Dessinée Potentiele - or, the Workshop for Potential Comics, best represented in the US by Matt Madden, Jason Little and Tom Hart). Modeled after the OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Literature Potentielle - workshop for potential literature) created by Raymond Queneau, the OuBaPo aimed to explore new ground for comics using, paradoxically, constraints as a creative motor. The OuBaPo published four books to date (the last one in 2004) all by the dominating force behind the project, Jean-Christophe Menu and L'Association publishing house. Even if engaged in other projects the work of Jochen Gerner is never very far from OuBaPian creative processes.

Jochen Gerner views himself as a draftsman who does comics among other things. Represented in France by Anne Barrault Panorama du Feu was part of Jochen Gerner's second exhibition at said art gallery in 2009 (the first one happened in 2006). The theme of the exhibition was the four elements: earth, air, water, fire. A year later L'Association published Panorama du feu (the "fire" part of the exhibition, of course) in a cardboard box, surrounded by a paper ribbon with the word "Guerre" (war) written on it, containing fifty-one booklets numbered from zero to fifty. Each booklet is the reworking of what's called in France the "petits formats" (the little formats), cheap, mass art comics imported mainly from the UK (published there by Fleetway) and sold in newsstands from the 1950s (or even earlier) until their decline in sales during the 1980s and disappearance in the early 1990s. The genres included in Panorama du feu are War, of course, but also Western, Espionage, and even a Tarzan look-alike produced in Italy, Akim. In each of these eight page booklets (cover and back cover included; booklet number zero has twelve pages with an introduction by Antoine Sausverd) Jochen Gerner used two creative strategies: (1) the cover was blacked-out with India ink leaving a title formed by expressions found in the book and the name of the collection plus explosions and signs (circles, crosses) in (not so) negative space; (2) the interior retained some didactic essays, advertisements and other paratexts published in the original comic books, plus what Thierry Groensteen called "reduction" in Oupus 1 (L'Association, January 1997): the stories were reduced to four, five or six panels (one per page).

In Panorama du feu Jochen Gerner chose visual rhymes (airplanes or trucks in all the panels, for instance). He also favored more abstract images and close-ups.

Besides being a non-conceptual reflexion (as Jochen Gerner stressed, saying that his is not a theoretical approach) on violent representations in petit format comics during the Cold War, what I find fascinating in the comic book reductions performed by Jochen Gerner is the contrast between said supposedly entertaining violence and a clear intention to be didactic including in the books many scientific essays. Below there's an unexpected encounter between something as frivolous as Bettie and Veronica (Archie is here called Robert, by the way) and yet another image of violence. By mixing didacticism and comicality with the violence of war, the violent message was somewhat undermined or, at least, balanced by a variety of things, advertisements included.

Given the fact that Jochen Gerner reduced whole stories to a few panels it's no surprise that many make little sense letting the reader with the strange sensation that something incomprehensible is going on (cf. below: infra-narrativity).

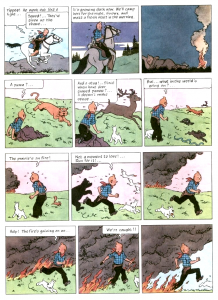

The blacking-out of covers and interior pages (as seen above: a détournement of Hergé's Tintin en Amérique - Tintin in America -, 1946 version) has its roots seven years before. In the above page the word "feu" (fire) appears (twice) and pictographs representing flames and smoke (plus a car and the words "poursuite" - "chase" -, and "route" - "road") are similar to the covers in Panorama du feu. A look below at Hergé's page blacked-out by Jochen Gerner in TNT en Amérique helps us to reach interesting conclusions:

Diegetically two things happen in this Tintin page: Tintin escapes a persecution and flees a fire. In the tradition of creating suspense at the end of every odd page Tintin is almost caught by the flames in the last panel. The persecution (by the baddies) is represented in TNT en Amérique by a car and the words "chase" and "road." In spite of Tintin riding a horse (the stereotype of the American cowboy imposes itself to a formulaic narrative) Jochen Gerner used a car pictogram to update the story. The animals on tiers two and three are almost ignored (the "almost" goes to the star pictograph, a symbol of trouble - emanata would have been more effective, maybe, but who am I to question Jochen Gerner's choices?, maybe he sees emanata as too blunt a sign?). Most of the attention goes to the fire with an ironic devil chasing the hero: can he be a villain destined to burn in hell's eternal flames in spite of his virtuous persona?

The general conclusion that we may extract from the TNT en Amérique example is that the two creative tactics described above (blacking-out and reduction) have the exact same result of reducing the deturned story to a skeleton.

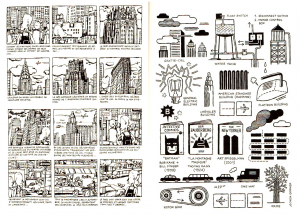

The image above shows, on the left, a page of Jochen Gerner's autobiographical book Courts-circuits géographiques; the image on the right shows the same page reworked for publication in XX/MMX (an anthology commemorating L'Association's 20th anniversary). As Jean-Christophe Menu noticed in his thesis La bande dessinée et son double (comics and their double, L'Association, 2011), the evolution from representational (even if caricatural) to ideographical is clear, but even the older page shows a tendency to what Thierry Groensteen called, in Bande dessinée récit et modernité (comics, narrative and modernity, Futuropolis, 1988) "the inventory" (a subset of his concept of the infra-narrative).

In Malus, as seen above, a silk-screened comic, Jochen Gerner illustrated real traffic disasters reported in newspapers. A creative tension is caused by the caricatural and schematic drawings depicting tragic events. A distance is created by the inadequate relation between form and content, or, to be more precise, the content isn't exactly what one would expect given the source material. An ironic Dadaistic distance pervades all of Jochen Gerner's work, but Malus is the height of this propensity. It shows Gerner's tendency to explore - and short-circuit; cf. the Betty and Veronica example above - violent undercurrents in the mediasphere. TNT en Amérique lays bare, by reduction, how violent Hergé's stories really are (TNT being, obviously, a reduction of Tintin's name and an explosive). The same happens in Panorama du feu.

As we can see below Panorama du feu is a dual object corresponding to its two lives in 2009 (in an art gallery) and 2010 (as a series of fifty one comic books):

In 2009 the fifty books were, as Jochen Gerner put it, like a giant battle ground as seen on a big control panel. Seeing the deturned covers behind glass encased comics come to mind. The act of reading is out of the question. On the other hand L'Association's edition does almost the opposite, readers have access to the booklets' content, but the ensemble is lost. Can these two forms of presentation be reconciled? I don't think so, but one of the best solutions, I think, involved Jochen Gerner. I'm talking about Salons de lecture (Reading Rooms), an exhibition at the La Kunsthalle in Mulhouse:

In Salons de lecture readers /viewers were invited to sit and read, as we can see above. As I said, reading and viewing can't be reconciled, but I like this Duchampian solution: it's a visual arts exhibition because the La Kunsthalle is a place where contemporary art is shown. Plus: there's the design with different colors for the six rooms available.

Here's Jochen Gerner's opinion:

Jochen Gerner was a founding member of the OuBaPo (Ouvroir de Bande Dessinée Potentiele - or, the Workshop for Potential Comics, best represented in the US by Matt Madden, Jason Little and Tom Hart). Modeled after the OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Literature Potentielle - workshop for potential literature) created by Raymond Queneau, the OuBaPo aimed to explore new ground for comics using, paradoxically, constraints as a creative motor. The OuBaPo published four books to date (the last one in 2004) all by the dominating force behind the project, Jean-Christophe Menu and L'Association publishing house. Even if engaged in other projects the work of Jochen Gerner is never very far from OuBaPian creative processes.

Les Vacances de l'OuBaPo (the vacations of the OuBaPo), Oupus 3, L'Association, October 2000, illustration by Jochen Gerner.

In Panorama du feu Jochen Gerner chose visual rhymes (airplanes or trucks in all the panels, for instance). He also favored more abstract images and close-ups.

Airplanes (in perfect order and in chaos) in booklet # 40 of Panorama du feu, L'Association, September 2010: visual rhymes.

Given the fact that Jochen Gerner reduced whole stories to a few panels it's no surprise that many make little sense letting the reader with the strange sensation that something incomprehensible is going on (cf. below: infra-narrativity).

Betty and Veronica run to join the French war effort during WWII? booklet # 33 of Panorama du feu, L'Association, September 2010: comicality undermines seriousness.

Page 38 of TNT en Amérique by Jochen Gerner, L'Ampoule, 2002.

Page 38 of Tintin in America as published in 1973 by Methuen (originally published in black and white in 1931 /32 and reworked by Hergé in 1946).

The general conclusion that we may extract from the TNT en Amérique example is that the two creative tactics described above (blacking-out and reduction) have the exact same result of reducing the deturned story to a skeleton.

On the left: page from Courts-circuits géographiques (geographical short-circuits), L'Association, 1997; on the right, the same page as reworked for XX/MMX, L'Association, 2010.

Malus by Jochen Gerner, Drozophile, 2002. A boon to a Ben-Day fetishist like me.

Left: Buck John # 105 (Buck Jones, I guess), Imperia, February, 1958; right: a deturned by black-out Buck John comic (not necessarily # 105, of course), Panorama du feu, L'Association, September 2010.

Up: Panorama du feu as exhibited in Anne Barrault's gallery, September 2009; down: Panorama du feu as a box containing fifty one booklets, L'Association, September 2010.

Salons de lecture, La Kunsthalle, Mulhouse, February 3 - April 3, 2011.

Here's Jochen Gerner's opinion:

Simply to place the boards adjacent to each other in a linear fashion is like trying to reproduce the phenomenon of reading a book. This can't be right. But the exhibition Reading Rooms plays effectively with the principle of the book on a flat surface. The effect in this exhibition is almost that of a wall placed horizontally on trestles. The exhibition design and the graphic systems used to mark the placement of the books, plus the captions printed on the table propel these books into another dimension.

Saturday, April 6, 2019

Monthly Stumblings #19: Fred

Le petit cirque (the little circus) by Fred.

Fred is the nom de plume and the nom the pinceau of Frédéric Othon Theodore Aristidès. You may have heard about him because of Pilote magazine and his most famous series, "Philemon" (or Philemon if we are talking about the albums). Before that though, Fred had a career behind him as a single-panel gag cartoonist and an absurdist comics artist in the pages of several magazines (the Mad inspired Hara-Kiri especially). It was in said mag that Fred published (from issue #38, April 1964, until issue #64, June 1966) his masterpiece "Le petit cirque" (or Le petit cirque if we're talking about the 1973, 1997 and 2012 album editions). The series, in short episodes of two pages each (with the exception of the first three pages), was also reprinted in Pilote magazine (it appeared in twenty eight issues from #701, April 1973, until #741, January 1974).

In 2012 an important retrospective of Fred's work, Le petit cirque included, was shown at the Angoulême comics convention in France (at the Hôtel Saint-Simon, to be exact). To celebrate the occasion Dargaud published a new remastered edition of Le petit cirque directly shot from the existing original art (which means that pages #8, 9, 26, 27, 36, 37 - three episodes - didn't receive the same treatment as the rest of the book; there's no discernible difference between those pages and all the others though; the editors didn't explain why this is so). Now I'm waiting for a new edition of Le journal de Jules Renard Lu Par Fred (Jules Renard's journal read by Fred) with the original page layouts recovered. I hope that someone at Flammarion reads my appeal.

Panel from page 53 of the 1997 edition of Le petit cirque by Fred.

The same panel as above from page 51 of the 2012 edition.

Fred himself said, remembering the series' first album edition in 1973:

The first two tiers of the first page of the series as it appeared in Hara-Kiri # 38, April 1964.

The same tiers published in the albums (in this case, the 2012 edition). As we can see the logo and the episode titles, when they existed, disappeared.

The first two panels of episode two (three in the albums) as published originally in Hara-Kiri # 39, May 1964.

The same panels as published in the 2012 album edition. The logo and episode title were removed, a paper and pencil texture was added (notice the glue smears captured by the photogravure).

We can find the prehistory of Le petit cirque in a couple of circus related cartoon gags, but we can also find it in a series of strange, imaginative professions created by Fred for Hara-Kiri: the knitter of savage balls; the bearded seller of cotton candy (barbe à papa); the representative of holes; the countryside licker of stamps; the celery grinder; the mirror fixer... In one of his "little jobs" Fred created the human time bomb. That's where the little circus really started: it was destined to be the album's second episode.

The little jobs: the countryside licker of stamps. Notice the Fredian twiggy tree and the wind. Hara-Kiri # 23, December 1962.

The first half of "L'audition"'s first page (the audition) with the human cannonball (the human time bomb appears in the page's second half), Hara-Kiri #37, March 1964. The little circus before the little circus: it is right there in the second panel.

But we may find the true origins of the little circus not only in time, but also in space, in what Fred calls Constantinople (aka Istanbul). Both of Fred's parents were Greek living in Turkey when WWI raged on and the war between the two countries was declared in 1919. They both emigrated to meet each other in Paris where Fred was born in 1931.

Fred, again:

The family that inspired Le petit cirque: from left to right: Eleni (Carmen), Yanis (Léopold), and little Fred (who, in the album, has no name); Trouville, 1930s.

Fred's iconography is very personal and explains the strange poetical power of Le petit cirque: the wind, the leafless trees, the circus, the peasants, the authorities, the mirror, the landscape, the city, etc... Apart from that what's great about Le petit cirque is its rhetorical complexity.

Le petit cirque, page 11 of the 2012 edition.

The above page gives the readers one of the keys to read Le petit cirque: the rhetorical reversal of the situations (the daily life of a patriarchal Mediterranean family is shown as circus acts). Another key is what I called, in Monthly Stumblings #16, the interpenetration rhetorical mode: two distant spaces meet in a third space where both may co-exist at the same time (more about that later). The last panel shows Fred's leafless trees with the wind blowing strongly from left to right expelling both the reader - the author too in a nostalgic statement about his childhood? - and the character out of the page (the sudden change of point of view from panel five to panel six shows that it's time to leave already). The overall atmosphere is scrawny and uncomfortable. The vanishing point in the last panel focus Carmen pulling the circus caravan (Fred explained the metaphor: "the caravan symbolizes the family and the head of the family is the wife"; needless to say that this doesn't convince me at all...). Notice how the horizon line gets lower and lower until we see a towering caravan getting out of reach. On pages 58 and 59 outraged peasants want to argue with Léopold and Carmen, but are overwhelmed when they find out that the caravan, despite its modest exterior appearance, is in reality a palace (not unlike Snoopy's doghouse). This, of course, is an hyperbole showing Fred's huge respect for his creatures.

Carmen discovers the violin tree in page 36 of the 2012 edition.

The violin tree is just one of the interpenetrations that I mentioned above. Others link circus people with animals (a clown is a rooster, etc...). The violin tree is the hope and the means to fulfill one's dreams. The problem is that Léopold, after picking one of the violins from the tree, breaks a string interrupting the process: the family is doomed never to improve their situation no matter how hard they try.

The first two panels of page 18 of Le petit cirque's 2012 edition. To the circus family the city is a menacing, blocky, empty space. Fritz Lang's expressionist Metropolis isn't far; an hyperbole, again.

Le petit cirque: second and third tiers of page 48 of the 2012 edition.

In the image above Carmen deflates an overblown bourgeois. The stereotype is a bit blunt, to say the least, but there's an interesting catch in the sequence: the relation between iconic and verbal expression. Fred puts an idea usually uttered in words ("she deflated him") into drawings. Something that isn't that usual in comics. The same thing happens in the rooster/clown interpenetration mentioned above: the clown is visually a clown; we only know that it is in reality a rooster because of what the characters say about him.

I could go on doing close readings of all the episodes of Le petit cirque (like the one in which Léopold and Carmen offer a wheelchair to their son and break his leg in order for him to enjoy his present - which he does, of course), but the above is enough, I guess...

In conclusion: the circus family wanders aimlessly in an inhospitable landscape, is harassed and hated by almost everybody else and they suffer setback after setback, but they continue their journey because they have to, winning a few small victories along the way... We only get to the sense of it all though after decoding the logic of the book which is the nonlinear, oblique logic of dreams.

Fred sets his little creatures in motion; second tier of Le petit cirque's 2012's edition's last page. Another narrative device: self-referentiality.

Fred is the nom de plume and the nom the pinceau of Frédéric Othon Theodore Aristidès. You may have heard about him because of Pilote magazine and his most famous series, "Philemon" (or Philemon if we are talking about the albums). Before that though, Fred had a career behind him as a single-panel gag cartoonist and an absurdist comics artist in the pages of several magazines (the Mad inspired Hara-Kiri especially). It was in said mag that Fred published (from issue #38, April 1964, until issue #64, June 1966) his masterpiece "Le petit cirque" (or Le petit cirque if we're talking about the 1973, 1997 and 2012 album editions). The series, in short episodes of two pages each (with the exception of the first three pages), was also reprinted in Pilote magazine (it appeared in twenty eight issues from #701, April 1973, until #741, January 1974).

In 2012 an important retrospective of Fred's work, Le petit cirque included, was shown at the Angoulême comics convention in France (at the Hôtel Saint-Simon, to be exact). To celebrate the occasion Dargaud published a new remastered edition of Le petit cirque directly shot from the existing original art (which means that pages #8, 9, 26, 27, 36, 37 - three episodes - didn't receive the same treatment as the rest of the book; there's no discernible difference between those pages and all the others though; the editors didn't explain why this is so). Now I'm waiting for a new edition of Le journal de Jules Renard Lu Par Fred (Jules Renard's journal read by Fred) with the original page layouts recovered. I hope that someone at Flammarion reads my appeal.

Panel from page 53 of the 1997 edition of Le petit cirque by Fred.

The same panel as above from page 51 of the 2012 edition.

Fred himself said, remembering the series' first album edition in 1973:

I was pleasantly surprised that time! When we took the pages out of the portfolio to print the album, we realized that the original art had yellowed. Time yellows everything, even the mementos hidden in the bottom of a suitcase. Gray had become sepia which added a melancholia of sorts. I love those atmospheres.As we can see above the 1997 edition reproduced the sepia tones. The lines are far from crisp though and many wash details were lost to resurface in the 2012 edition only. The latter's matte paper retains some of the beige flavor that pleased Fred. Since Le petit cirque is a comics masterpiece I would say that this edition is one of last year's most important comics related events. Unfortunately it passed virtually unnoticed.

The first two tiers of the first page of the series as it appeared in Hara-Kiri # 38, April 1964.

The same tiers published in the albums (in this case, the 2012 edition). As we can see the logo and the episode titles, when they existed, disappeared.

The first two panels of episode two (three in the albums) as published originally in Hara-Kiri # 39, May 1964.

The same panels as published in the 2012 album edition. The logo and episode title were removed, a paper and pencil texture was added (notice the glue smears captured by the photogravure).

The little jobs: the countryside licker of stamps. Notice the Fredian twiggy tree and the wind. Hara-Kiri # 23, December 1962.

The first half of "L'audition"'s first page (the audition) with the human cannonball (the human time bomb appears in the page's second half), Hara-Kiri #37, March 1964. The little circus before the little circus: it is right there in the second panel.

Fred, again:

It was the first time that I did something solid and everything happened naturally, the ideas, the emotions. Maybe because it's the story of people without roots, like my parents. After leaving Constantinople they traveled a lot too and it was my father who inspired me to create Léopold. [...] The Carmen of Le petit cirque is dark-haired and thin while my mother had brown hair and was rather plumpish, but she inspired me nonetheless.

The family that inspired Le petit cirque: from left to right: Eleni (Carmen), Yanis (Léopold), and little Fred (who, in the album, has no name); Trouville, 1930s.

Le petit cirque, page 11 of the 2012 edition.

Carmen discovers the violin tree in page 36 of the 2012 edition.

The first two panels of page 18 of Le petit cirque's 2012 edition. To the circus family the city is a menacing, blocky, empty space. Fritz Lang's expressionist Metropolis isn't far; an hyperbole, again.

Le petit cirque: second and third tiers of page 48 of the 2012 edition.

I could go on doing close readings of all the episodes of Le petit cirque (like the one in which Léopold and Carmen offer a wheelchair to their son and break his leg in order for him to enjoy his present - which he does, of course), but the above is enough, I guess...

In conclusion: the circus family wanders aimlessly in an inhospitable landscape, is harassed and hated by almost everybody else and they suffer setback after setback, but they continue their journey because they have to, winning a few small victories along the way... We only get to the sense of it all though after decoding the logic of the book which is the nonlinear, oblique logic of dreams.

Fred sets his little creatures in motion; second tier of Le petit cirque's 2012's edition's last page. Another narrative device: self-referentiality.

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

Monthly Stumblings #18: James Edgar, Tony Weare

“The Territory” by James Edgar and Tony Weare

“Matt Marriott” is, with “Randall, The Killer” by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Arturo del Castillo, the best Western in comics form. This may seem like damning with faint praise because the overall quality of comics Westerns is truly appalling (with the American ones in pamphlets and a newspaper comic strip like “The Cisco Kid” among the worst…). That’s far from being the truth though: both comics series include some of the greatest comics ever published. Unfortunately both share the same disdain from publishers and readers alike. “Randall” (published mainly in the Argentinean comic book Hora Cero Suplemento Semanal [zero hour weekly supplement], issues # 1 – 65: 1957/58, is long out of print; my attempt to bring it back to life failed because there’re problems among some copyright holders, or something…). So, in two words: no Randall. “Matt Marriott” is a British newspaper comic strip that ran in the [London] Evening News from 1955 until 1977. We know who the copyright holders are, but, in a similar attempt, I’ve learned that they can’t find the printing plates anywhere. In view of the fact that the original art was scattered around we just have Edgar’s and Weare’s masterpiece on microfilm in the British Library Newspapers, so, ditto: no Matt Marriott.

That’s how the amnesiac art of comics loses another chunk of its memory. It’s a huge shame that, on top of it all, it is one of its best parts…

Marriott and Horn are expelled for defending the Indians. (I decided to illustrate this Stumbling with original art scans only. The image is a good metonymy of how “Matt Marriott” was barred from the history of comics for not being a children’s comic.) “The Territory,” Evening News, 1973.

As for the scripter, James Edgar, no one knows what he thought because of two facts: (1) comics fans like Denis Gifford (the only ones writing about comics at the time) suffered from acute childhood nostalgia syndrome: to them only old comics magazines like Comic Cuts were worthy of attention (even so Gifford wrote a 1971 ridiculously sparse “history” of British newspaper comics); (2) scripters weren’t even credited, let alone interviewed.

Anyway, in the International Journal of Comic Art (Vol. 9, # 1, Spring 2007) and elsewhere (Nemo Vol. 2, # 22, June 1996) I suggested the concept of the “absent hero.” A kind of Greek chorus that needs to be there for commercial reasons, but doesn’t intervene much in the action to avoid the cliché of winning the day every time. That’s what happens to Matt Marriott and Powder Horn in some episodes, but not in “The Territory,” or, at least, not completely. Looking at a fight between Marriott and the Miniconjou Indians is like looking at a rigged boxing match.

Almost every other narrative aspect in the series differ from more traditional genre tropes. The characterization, for instance, gives us a fresco of 19th century North American people that is unmatched anywhere. I’ll give you a small sample below.

In a now familiar procedure (to the readers of the Stumblings, that is), the shadows on the exterior of the face, mirror the characters’ inside feelings. The procedure was first called to my attention by Alain Jaubert in his great Arte TV series: Palettes. “When the Bear Runs,” Evening News, 1972.

In “Matt Marriott” there are miners and soldiers, hunters and merchants, politicians and businessmen, herd drivers and outlaws, lawyers and doctors, bankers and lawmen, etc… Women are homemakers, sex workers and boarding house keepers. Tony Weare’s great characterizations are only matched by James Edgar’s colorful characters and colorful language. Doc Massey in “Marshall of Fireweed” (1959), said to Matt: “How now my tall pillar of rectitude. There’s a puritan streak in you that doesn’t sit well with that gun on your hip.” The same Doc Massey described his situation after being mortally wounded as “being a little drunk with valediction.” “Powder” Horn wasn’t that bad with words either, as seen above in fig. 1 and in the below panel (in an old comics tradition the direct discourse is reproduced in pronunciation spelling).

Violence had true consequences in “Matt Marriott.” Notice how Tony Weare could convey shock and dismay in the background characters’ faces with just a few brush strokes. “Trail Drive,” Evening News, 1965.

“Trail Drive,” Evening News, 1965.

The grin in Horn’s face is explained by the fact that he’s a racist who feels pleasure in killing an Indian. This is one of those occasions in which Tony Weare would subvert the script – in cahoots with James Edgar or not, we’ll never know – going completely against the grain. The narrative implications of this simple drawing are huge. To say it in mass art lingo: the hero’s sidekick is suddenly a villain which means that the hero kills innocent people to save a guilty character. That’s what I call a good drawing (a drawing with meaning): technical skills only seems like a poor “set” of criteria to me. “The Territory,” Evening News, 1973.

Sam Folsom and ‘Relish’: The sexual politics of the “Matt Marriott” series could be a post of its own. “The Territory,” Evening News, 1973.

Light and shadows and shades of gray. “Gospel Mary,” Evening News, 1973.

“Matt Marriott” is, with “Randall, The Killer” by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Arturo del Castillo, the best Western in comics form. This may seem like damning with faint praise because the overall quality of comics Westerns is truly appalling (with the American ones in pamphlets and a newspaper comic strip like “The Cisco Kid” among the worst…). That’s far from being the truth though: both comics series include some of the greatest comics ever published. Unfortunately both share the same disdain from publishers and readers alike. “Randall” (published mainly in the Argentinean comic book Hora Cero Suplemento Semanal [zero hour weekly supplement], issues # 1 – 65: 1957/58, is long out of print; my attempt to bring it back to life failed because there’re problems among some copyright holders, or something…). So, in two words: no Randall. “Matt Marriott” is a British newspaper comic strip that ran in the [London] Evening News from 1955 until 1977. We know who the copyright holders are, but, in a similar attempt, I’ve learned that they can’t find the printing plates anywhere. In view of the fact that the original art was scattered around we just have Edgar’s and Weare’s masterpiece on microfilm in the British Library Newspapers, so, ditto: no Matt Marriott.

That’s how the amnesiac art of comics loses another chunk of its memory. It’s a huge shame that, on top of it all, it is one of its best parts…

Throughout the series Matt Marriott and his

sidekick Jason “Powder” Horn, fulfill their odyssey wandering the West

of the United States in a still divided (social wounds not totally

healed) post Civil War. It’s a country in which the farmers’ settlements

are competing with the ranch owners’ land (the Fence Cutting Wars).

Other times the narrative focus is the railroad construction and the

decimation of buffalo herds. Still in other occasions the social

background is the Indian Wars. That’s the case in “The Territory”; not

war exactly, I mean, but serious racial tensions that lead to blood

shed.

Marriott and Horn are expelled for defending the Indians. (I decided to illustrate this Stumbling with original art scans only. The image is a good metonymy of how “Matt Marriott” was barred from the history of comics for not being a children’s comic.) “The Territory,” Evening News, 1973.

But let’s leave the territory (Montana)

alone for a while to give a general look at the series first. I’ll start

by putting what I don’t like about it out of the way: the usual

formulaic nonsense of mass art genre Westerns (the American monomyth,

basically, or something even more boneheaded). Unfortunately it exists

even in “Matt Marriott” and Tony Weare knew it and abhorred it (Ark, 1990, 47):

Me too!I would have liked the characters to have been fallible, but, of course, being cowboys they have to be infallible. If there was a scene where Matt and Powder were camping out in the bush at night and they heard a noise, Powder would ask Matt if that noise meant there were Indians. Matt would calmly announce that it was an owl, and he’d be right. In another episode, Powder would say it was an owl and Matt would say it was Indians, and Matt would be right again. I always wished that they’d change it around for once. That side of cowboys is very boring. It’s the same with Batman. He can’t make a mistake either. […] In the gunfights the baddies shoot ten bullets and they all miss whilst the goodies shoot one bullet and it’s on target. I hated that side of it.

As for the scripter, James Edgar, no one knows what he thought because of two facts: (1) comics fans like Denis Gifford (the only ones writing about comics at the time) suffered from acute childhood nostalgia syndrome: to them only old comics magazines like Comic Cuts were worthy of attention (even so Gifford wrote a 1971 ridiculously sparse “history” of British newspaper comics); (2) scripters weren’t even credited, let alone interviewed.

Anyway, in the International Journal of Comic Art (Vol. 9, # 1, Spring 2007) and elsewhere (Nemo Vol. 2, # 22, June 1996) I suggested the concept of the “absent hero.” A kind of Greek chorus that needs to be there for commercial reasons, but doesn’t intervene much in the action to avoid the cliché of winning the day every time. That’s what happens to Matt Marriott and Powder Horn in some episodes, but not in “The Territory,” or, at least, not completely. Looking at a fight between Marriott and the Miniconjou Indians is like looking at a rigged boxing match.

Almost every other narrative aspect in the series differ from more traditional genre tropes. The characterization, for instance, gives us a fresco of 19th century North American people that is unmatched anywhere. I’ll give you a small sample below.

The Indians are no exception as we can see in the following great panel.

In a now familiar procedure (to the readers of the Stumblings, that is), the shadows on the exterior of the face, mirror the characters’ inside feelings. The procedure was first called to my attention by Alain Jaubert in his great Arte TV series: Palettes. “When the Bear Runs,” Evening News, 1972.

In “Matt Marriott” there are miners and soldiers, hunters and merchants, politicians and businessmen, herd drivers and outlaws, lawyers and doctors, bankers and lawmen, etc… Women are homemakers, sex workers and boarding house keepers. Tony Weare’s great characterizations are only matched by James Edgar’s colorful characters and colorful language. Doc Massey in “Marshall of Fireweed” (1959), said to Matt: “How now my tall pillar of rectitude. There’s a puritan streak in you that doesn’t sit well with that gun on your hip.” The same Doc Massey described his situation after being mortally wounded as “being a little drunk with valediction.” “Powder” Horn wasn’t that bad with words either, as seen above in fig. 1 and in the below panel (in an old comics tradition the direct discourse is reproduced in pronunciation spelling).

Tony Weare’s drawing style evolved from a

more conventional naturalism to a rough impressionism that’s quite

impressive in its mixture of looseness and preciseness. Besides admiring

Weare’s uncanny ability to lay out a scene it’s amazing how he could

instill life and expression to a couple of brush strokes depicting a

face. Ditto for the body language.

Violence had true consequences in “Matt Marriott.” Notice how Tony Weare could convey shock and dismay in the background characters’ faces with just a few brush strokes. “Trail Drive,” Evening News, 1965.

Tony Weare was also a master at shading. He

was able to depict any moment of day or night simply by the intelligent

use of black, white and the way he did the hatching and cross-hatching. I

particularly like his dim lunar light.

“Trail Drive,” Evening News, 1965.

Other times I just like the nice touch of the little dog that no one seems to notice.

“Matt Marriott” was a daily strip published

six days a week. Most of the strips had three panels which Tony Weare

varied from medium shot to close up, varying the size of the panels

accordingly (the closer the distance between the picture plane and the

“object,” the smaller the panel; this is what Benoït Peeters calls: the

rhetorical use of the page). This wasn’t a rigid rule, or anything, of

course. Below, for instance, is an establishing shot in a two, not three, panel

daily.

Like the Fates of old James Edgar was great

at weaving plots. In his stories situations build on situations in a

relentless pace. Actions have (sometimes brutal) consequences. In “The

Territory” (a “Matt Marriott” story arc that appeared in the Evening News between

May 4, 1973 and August 23 of the same year) a series of unfortunate

events lead to the death of a young Indian followed by the kidnapping of

“Powder” Horn (the Miniconjou want to punish him) and a hazardous

rescue by Matt Marriott and friend Sam Folsom; a man who lives with an

Indian woman and knows a lot about Indian culture and the hunger inside

the reservations.

The grin in Horn’s face is explained by the fact that he’s a racist who feels pleasure in killing an Indian. This is one of those occasions in which Tony Weare would subvert the script – in cahoots with James Edgar or not, we’ll never know – going completely against the grain. The narrative implications of this simple drawing are huge. To say it in mass art lingo: the hero’s sidekick is suddenly a villain which means that the hero kills innocent people to save a guilty character. That’s what I call a good drawing (a drawing with meaning): technical skills only seems like a poor “set” of criteria to me. “The Territory,” Evening News, 1973.

Sam Folsom and ‘Relish’: The sexual politics of the “Matt Marriott” series could be a post of its own. “The Territory,” Evening News, 1973.

As in any other Western there are lots of

evil doers in “Matt Marriott” (in “The Territory” the enemy is racism

and the unscrupulous store keeper who sold alcohol to the young

Indians), but Manicheism is softened as much as possible because Tony

Weare avoided the “bad guy” stereotype and James Edgar gave plausible

motivations to his characters. If you want to know “whom” the real enemy

is, read below: it’s one of my favorite comic panels of all time.

Light and shadows and shades of gray. “Gospel Mary,” Evening News, 1973.

Wednesday, March 6, 2019

Sunday, February 24, 2019

Monthly Stumblings #17: Marco Mendes

Diário Rasgado [torn diary] by Marco Mendes

(1) Politics

What do you see above?

A dark, moonless night... two buildings on the middleground, more on the background on the right hand of the drawing... a wall and what seems to be the remains of a wooden door... a mural (or graffiti, if you prefer) on said wall... a wrecked car...

Examining the mural we can see people in some kind of demonstration. The one on the right is waving a flag...

If the sky is pitch black what is the light source? Most probably an out of frame street lamp. This is, unmistakably, the inospitable landscape of the human beehives: proletarian suburbia, the projects...

So far so good, right? My point though is that images aren't as universal as some people seem to think. In order to fully decode them some context is needed. In this particular case you may also have guessed that this is political art... And highly sophisticated political art at that. Marco Mendes is a Portuguese comics artist and this is the last, and, not the most powerful, by any means, image of his uneven (more on that later), but great book Diário Rasgado...

Going back to the image above lets concentrate now on the wall. What's it doing there? If we go back a century or so Portugal's economy relied mostly on backward agriculture. Portugal's Industrial Revolution was insipid at best. Forty eight years (1926 - 1974) of a right wing conservative regime didn't help to change anything. On the contrary: Salazar, the dictator, was an extremely religious fellow who wanted a country culturally stuck on the ancien régime. The popaganda of his time spread the image of an idylic rural community life (pretty much like the apple pie visions of America).

The above watercolor is a perfect example of Salazar's ideology: after a day's (or a morning's) work the rural worker (using an archaic tool) comes back to his patriarchal, poor, but highly organized and clean, happy home. At the center of everyday life, holding the boat and assuring law and order, were the Catholic and State religions (look through the window at the Portuguese flag on top of a Medieval castle representing our glorious forefathers). Needless to say, such popaganda did hide a grim reality of exploitation, hunger, and gender inequality.

But I digress, maybe?... What about the wall in Marco Mendes' drawing, then? It's there because in the above described rural Portugal some wealthy families owned farms around the main cities. In time those farms were dismantled and invaded by greedy real estate entrepeneurs. Projects for the rich and not so rich multiplied like mushrooms because of a complete absense of planning policies (not to mention political corruption). Poor rural workers fled hunger-ridden rural areas hoping for a better urban life and each one of them needed a place to live after all (it's a well known story everywhere). Maybe that wall is a standing mute witness to those old days when beautiful farms were part of the urban landscape. Because of the mural on it it's also a witness to radical changes in Portuguese society after the Revolution of April 25, 1974.

Marco Mendes used a bit of a poetical license in his drawing because the murals of the revolution didn't survive. Maybe there's one or two still around, who knows?, but I don't think so. I can't imagine one in 2012 at least. For a couple of reasons: a left wing mural, reminincent of the Maoist one above has a different reading in Beijing and Lisbon. It can only mean what I think it means in Diário Rasgado, shattered hopes, because we are suffering by far the worst dictatorship that ever existed: the dictatorship of the financial markets, the dictatorship of the wolves disguised as lambs; the dictatorship of the Plutocracies disguised as Democracies. In Beijing the image could mean the exact same thing with a crucial difference: the people could say with propriety: beware with what you wish for!... Even if no one believes in future times of milk and honey now, the fact is that many Idealistic people did back then just to slowly fall into the (as Luís de Camões - 16th century – put it in one of the best poems ever written) "disarrangement of the world" again...

Two final notes: the woman on the mural above should liberate herself (getting rid of the pinafore apron) before trying to liberate others; Marco's drawing is a Deleuzian image-time linking the past and the future (time is cyclical): the wrecked car may be warning us that popular upheavals, like the ones that happened all over France in 2005 and the UK in 2011, are bound to happen in Portugal.

(2) Autobiography?

Well... not exactly...

It's true that the title of Marco's book mentions a diary... Plus: the characters who appear in the book are the personas of Marco, his friends (Miguel Carneiro, with whom Marco co-founded A Mula - the mule - art collective among them) and girlfriend, Lígia Paz, but that's almost it... Marcos' private life certainly inspires him, but that's true for every artist, so, there's almost no autobiography in Diário Rasgado (the exceptions being the stories including his family, his grandfather, mainly). Maybe Lynda Barry's autobiofictionalography is what I'm talking about, after all... It doesn't really matter though... We've long past those maverick days in which autobio meant being a mature and serious comics artist.

Marco Mendes' first book (a mini-comic), Tomorrow The Chinese Will Deliver the Pandas (June, 2008), was published in English with translations by Pedro Moura and Elisabete Pinto. There's an imediacy in his first work that, as Lígia Paz put it in "The Introduction [to said mini-comic] Marco Made Me Write":

The small but significant differences between the two versions of the same page above are also symptoms of two different editorial policies. The first page (which can also be seen in Marco Mendes' blog) is more messy: there are no gutters, graphic noise wasn't cleaned up. The original layout was destroyed in the book version (the page was cut in half to become two landscape formatted pages); everything is a bit more clean. It's the difference between a DIY punk aesthetic and a more professional, slicker look.

And yet... Even as early as 2007, there are quiet, melancholy moments in Marcos' oeuvre. His better work to date, done in the last couple of years, was created in that tone. (To be perfectly candid about it, even if I find Marco's earlier work fine enough this post wouldn't probably exist without the quality leap that are his amazing, more recent, color, mostly wordless, pages.)

Asked what genre interested him more, humor or drama, Marco answered: "They're both too close. I see no way of separating them." What we can infer from his words is that Marco Mendes is attracted to pathos (see below)... Even so, pure drama also happens, but Marcos manages to avoid sentimentality...

At some point Marco started to mostly use a regular layout of four panels in which the last one is a kind of punch line. He prepares it by developing a situation which he then procedes to twist a bit at the end (a process that's akin to Usamaru Furuya's four panel comic Palepoli). In "Socialist" above he used a palette of warm slightly sickly colors and changing points of view to convey movement and disorientation. (Other times the city is a cold pale blue - see below.) Since Edward Hopper is one of Marcos' biggest influences I can't think of many comics artists who can convey as well as he does the feeling of loneliness in a big city. The self-deluded beggar, thinking that he's entitled to a coin because he's a socialist is one of those things that, I suspect, can't be created from scratch (life has a lot more imagination than we do)... I may be wrong though, of course...

In "Departure" Marcos used the visual idea of shadowing the face of his character to convey his state of mind. Between him and his girlfriend we know who lost the most emotionaly when they broke up...

(1) Politics

Marco Mendes, Diário Rasgado, May 2012.

A dark, moonless night... two buildings on the middleground, more on the background on the right hand of the drawing... a wall and what seems to be the remains of a wooden door... a mural (or graffiti, if you prefer) on said wall... a wrecked car...

Examining the mural we can see people in some kind of demonstration. The one on the right is waving a flag...

If the sky is pitch black what is the light source? Most probably an out of frame street lamp. This is, unmistakably, the inospitable landscape of the human beehives: proletarian suburbia, the projects...

So far so good, right? My point though is that images aren't as universal as some people seem to think. In order to fully decode them some context is needed. In this particular case you may also have guessed that this is political art... And highly sophisticated political art at that. Marco Mendes is a Portuguese comics artist and this is the last, and, not the most powerful, by any means, image of his uneven (more on that later), but great book Diário Rasgado...

Going back to the image above lets concentrate now on the wall. What's it doing there? If we go back a century or so Portugal's economy relied mostly on backward agriculture. Portugal's Industrial Revolution was insipid at best. Forty eight years (1926 - 1974) of a right wing conservative regime didn't help to change anything. On the contrary: Salazar, the dictator, was an extremely religious fellow who wanted a country culturally stuck on the ancien régime. The popaganda of his time spread the image of an idylic rural community life (pretty much like the apple pie visions of America).

Jaime Martins Barata, Salazar's Lesson: God, the Fatherland, Family, the Trilogy of National Education, 1938.

But I digress, maybe?... What about the wall in Marco Mendes' drawing, then? It's there because in the above described rural Portugal some wealthy families owned farms around the main cities. In time those farms were dismantled and invaded by greedy real estate entrepeneurs. Projects for the rich and not so rich multiplied like mushrooms because of a complete absense of planning policies (not to mention political corruption). Poor rural workers fled hunger-ridden rural areas hoping for a better urban life and each one of them needed a place to live after all (it's a well known story everywhere). Maybe that wall is a standing mute witness to those old days when beautiful farms were part of the urban landscape. Because of the mural on it it's also a witness to radical changes in Portuguese society after the Revolution of April 25, 1974.

Anonymous political mural in Lisbon, 1977. Photo copyright Yves Benaroch.

Two final notes: the woman on the mural above should liberate herself (getting rid of the pinafore apron) before trying to liberate others; Marco's drawing is a Deleuzian image-time linking the past and the future (time is cyclical): the wrecked car may be warning us that popular upheavals, like the ones that happened all over France in 2005 and the UK in 2011, are bound to happen in Portugal.

(2) Autobiography?

Well... not exactly...

It's true that the title of Marco's book mentions a diary... Plus: the characters who appear in the book are the personas of Marco, his friends (Miguel Carneiro, with whom Marco co-founded A Mula - the mule - art collective among them) and girlfriend, Lígia Paz, but that's almost it... Marcos' private life certainly inspires him, but that's true for every artist, so, there's almost no autobiography in Diário Rasgado (the exceptions being the stories including his family, his grandfather, mainly). Maybe Lynda Barry's autobiofictionalography is what I'm talking about, after all... It doesn't really matter though... We've long past those maverick days in which autobio meant being a mature and serious comics artist.

Marco Mendes' first book (a mini-comic), Tomorrow The Chinese Will Deliver the Pandas (June, 2008), was published in English with translations by Pedro Moura and Elisabete Pinto. There's an imediacy in his first work that, as Lígia Paz put it in "The Introduction [to said mini-comic] Marco Made Me Write":

In [Marcos'] comics work, the exploration goes to the rhythmic possibilities inherent to the format, the drawings are more explosive, emotional, and surprisingly funny. There is a vivid concern in letting words and events flow, in a continuous and frequently corrected, scratched, and unaltered text, as if there is no [erasing] rubber.The drawing is sketchy and the little vignettes describe what happens in a house where bohemian art students live. The language is often coarse. Unfortunately some homophobia (still pervasive in Portuguese society), ableism and misogyny rear their ugly heads in Marco's friends' and girlfriend's jokes. A light humor and a friendly atmosphere is the general tone of these early strips (Lígia Paz, again).

There was a house [...] with a mythical living room: the setting of multiple parties, a ping-pong table, a famous sofa where so many have slept and [have] been portrayed, not to mention the walls, covered with drawings and several forms of confessions. [...] In all the rawness of his social realism, without tricks or self-complacency, the representations and portraits of the surrounding friends are also a testimony of our current times and of his generation. There is also a very clear sense of sharing, identity and belonging to a community, united by common values, experiences, and eighty cent beer.Lígia also mentions the "distance between the portrayed individual and the fictional character." Which, methinks, is revealing and should be used to describe autobio artists. As Arthur Rimbaud put it: "je est un autre" ("me is another").

Marco Mendes, Tomorrow The Chinese Will Deliver the Pandas, June 2008.

Marco Mendes, Diário Rasgado, May 2012.

And yet... Even as early as 2007, there are quiet, melancholy moments in Marcos' oeuvre. His better work to date, done in the last couple of years, was created in that tone. (To be perfectly candid about it, even if I find Marco's earlier work fine enough this post wouldn't probably exist without the quality leap that are his amazing, more recent, color, mostly wordless, pages.)

Asked what genre interested him more, humor or drama, Marco answered: "They're both too close. I see no way of separating them." What we can infer from his words is that Marco Mendes is attracted to pathos (see below)... Even so, pure drama also happens, but Marcos manages to avoid sentimentality...

In Barcelona: "Socialist: 'Give me a coin/ please... I'm/ a socialist/ I have no/ apartment, I/ can't work...' /'a coin please' /'I'm/ a socialist, a /coin please...'/ 'I'm a socialist...'," Diário Rasgado, May 2012.

Melancholia: The ending of a long distance relationship: "Departure," blog post, September 16, 2010.

In "Departure" Marcos used the visual idea of shadowing the face of his character to convey his state of mind. Between him and his girlfriend we know who lost the most emotionaly when they broke up...

Marco Mendes, "Mutiny," blog post, December 19, 2011. An Edward Hopper inspired shoe shop after a riot: another example of urban pathos?

A zoom out, but can we really escape these non-places (as Marc Augé called them)? Marco Mendes, Diário Rasgado, May 2

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)